Ahhh, television. Pioneered by Philo Taylor Farnsworth in 1927. Such humble beginnings as the passion project of an inventor who sought to revolutionize entertainment as we knew it. By the 1939 World’s Fair, the president of RCA, David Sarnoff, unveiled the first commercial publicly accessible television broadcast. By the 1950’s the medium would become the dominant form of home entertainment, supplanting broadcast radio. In its infancy, television often abided adaptations of one act plays, such as the inaugural program to ever air over broadcast waves, 1929’s The Queen’s Messenger by J. Harley Manners.

Television was in its incubation stage as we hurtled ever closer to the Second World War. The ’30s and early ’40s were an era of radio dominance, as the earliest TV networks such as NBC only offered 15 hours of programming a week. Said offerings typically ranged from straight dramas to lighthearted comedies (proto-sitcoms). In 1946, the UK’s Pinwright’s Progress was recorded as the first ever proper situational comedy to hit the airwaves. The US would follow a year later with Mary Kay and Johnny. In a post-World War II landscape, television had proven its mettle as the go-to for leisurely entertainment. 1951 would see the debut of I Love Lucy, Lucille Ball’s seminal sitcom classic that would endure over 180 half-hour episodes over the course of six “seasons.”

At the time, “seasons” did not exist in the same cultural context in which they do now. To even call them seasons is to be slightly misleading. We only do so retroactively. At the time, the word simply denoted a batch of episodes made within a particular production cycle; the situational comedy’s episodic nature lent to its stakes being reset by the end of the episode. On the whole, the genre was far less known for its ability to dish out long-form storytelling than it was for being the perfect launchpad for a good laugh in the now. This sitcom sensibility would continue in its television dominance in the years to follow – from Leave it to Beaver, The Andy Griffith Show, all the way to The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, only ever slightly increasing in serialized stakes that would continue to have any lasting bearing on the overall narrative trajectory of the series.

Enter: 1990’s Twin Peaks. David Lynch and Mark Frost set out with a single question that would revolutionize television as we knew it – Who killed Laura Palmer? The fictional small town of Twin Peaks (based on Snoqualmie, Washington) is the embodiment of the dark, brimming underbelly of the American consciousness. And moreover, a stalwart, earnest attempt at long-form serialized storytelling wherein each episode directly followed the events of the one prior. And to Lynch’s surprise (and ABC’s delight), Twin Peaks skyrocketed to immediate pop cultural fame. The central question had so fully integrated itself into the collective zeitgeist that Mark Frost was brought before Oprah to have the American audience cast their votes on who they think murdered the beloved homecoming queen.

Blazing viewership numbers and a trusty primetime slot made Twin Peaks television’s first true dosage of Event TV. Everyone would be dissecting and theorizing by the water cooler the following Monday. The show’s first season consisted of a light eight episodes in total (put a pin in that), crescendoing in the thrilling finale, “The Last Evening,” which led to many storylines culminating, and leaving the viewers on a tantalizing cliffhanger. With the overnight success of this truly unconventional show – one that upended the sitcom as the predominant form of television programming and paved the way for a Golden Age of TV – ABC renewed Twin Peaks for a much longer, 22 episode second season. It’s here where there are a handful of production issues that led to a troubled sophomore outing (Lynch would hand the reins to Frost whilst overseeing the Nicolas Cage-led Wild At Heart). Prior to his absence, the network leveraged an ultimatum at Lynch – reveal the identity of the killer by the next seven episodes, or ABC pulls the plug on the whole show.

Lynch never intended for the mystery to be spelled out for the viewer; he only hoped to leave enough of a breadcrumb trail as to where they could figure it out for themselves, but the network pressured him to offer the audience a concrete resolution. By the time he left, the killer’s identity would be known to the world, and it would mark the end of a three act structure within the 22 episode season. What followed was Frost and the writer room improvising a new direction for the show – a tailspin of a 10 episode freefall that fans often refer to simply as “The Lull.” Lynch’s return to the show stands in stark, immediate contrast. Our lead detective, the affable, quirky Special Agent Dale Cooper, has been rudderless after learning of Palmer’s killer. He’s “gone native” in this outwardly charming small community, but he has had no impetus to truly remain there. That is, until Lynch ramps up the stakes considerably by introducing a personal villain from Cooper’s life – Windom Earle. The final third of the season feels like such a welcome return to form, winding up to inarguably the most brain-melting finale one could ever witness firsthand in 1991 – “Beyond Life and Death” – featuring a 20 minute uncut odyssey the likes of which TV at the time could simply never have dreamt up in their wildest imaginations. Lynch leans full supernatural, and it is a thrilling swing for the fences, ending the season on a chilling note.

And then.

ABC never renewed Twin Peaks.

Or at least so the story would go for some time. David had plans for this special universe he helped bring to life, and the next stage of the show came in the form of a filmatic trilogy, the likes of which would never fully come to fruition. The first entry would be Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me, a daring prequel to the beloved series, reliving Laura Palmer’s last seven days through her own eyes, elevating her from object of the series to subject of her own narrative. I will never forgive the audience that infamously walked out of the premiere at Cannes, as they unwittingly nixed the resolution of the trilogy. The world would never see Twin Peaks: Blue Rose Society, nor the final unnamed film. Only 25 years later would we revisit the small town of Twin Peaks with the 18-part summer epic, The Return. But all in all, the legacy of Twin Peaks will forever be one that shifted the cultural sensibility of a season towards long-form storytelling. We simply would not have the endless bevy of prestige dramas today without the framework that Twin Peaks carved out for us. The television “season”, as it once existed, no longer merely meant a production batch; it would indicate a more intentional chapter in a more intentional story.

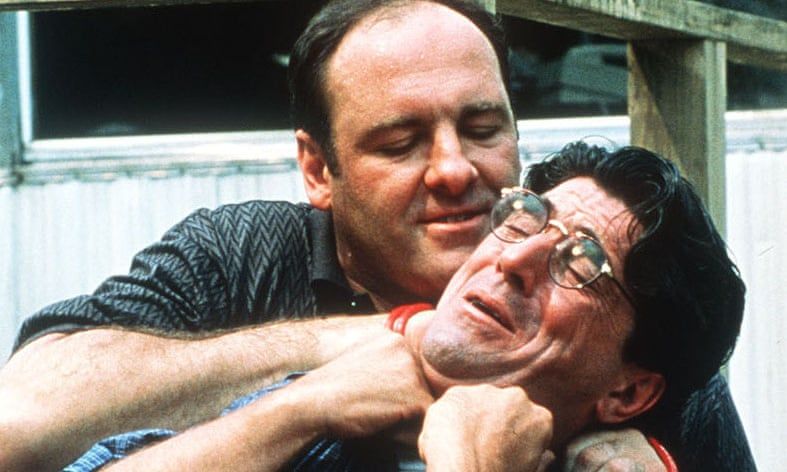

1999 would see HBO’s premier mob drama, The Sopranos, continuing the legacy of Twin Peaks in notably moving the serialized needle forward. David Chase’s savvy, sexy, snarling story about a mob boss enduring therapy as he confronts the existential ennui of his everyday life would enshrine the term “Prestige TV.” It was the kind of show you made sure you cleared your schedule for; over the course of 86 episodes over six thrilling seasons, The Sopranos became a cornerstone of television as a worthy medium of genuine, artful entertainment. Discussions would rage about cinema remaining the loftier medium, but Davids Lynch & Chase injected their cinematic inclinations into their own respective shows such that they elevated TV’s standing as a whole with it. No longer did you need to leave the comfort of your home to find grand, engrossing stories with larger-than-life characters. You could simply remain on the couch and tune into six of the finest seasons that television would have to offer. Season length on The Sopranos typically ran to a lucky 13 episodes – a benchmark that television would continue to drift away from as we enter more modern times. Its final season had been comprised of 21 episodes broken into two halves – a new convention whose impact bears reverberations to this very day.

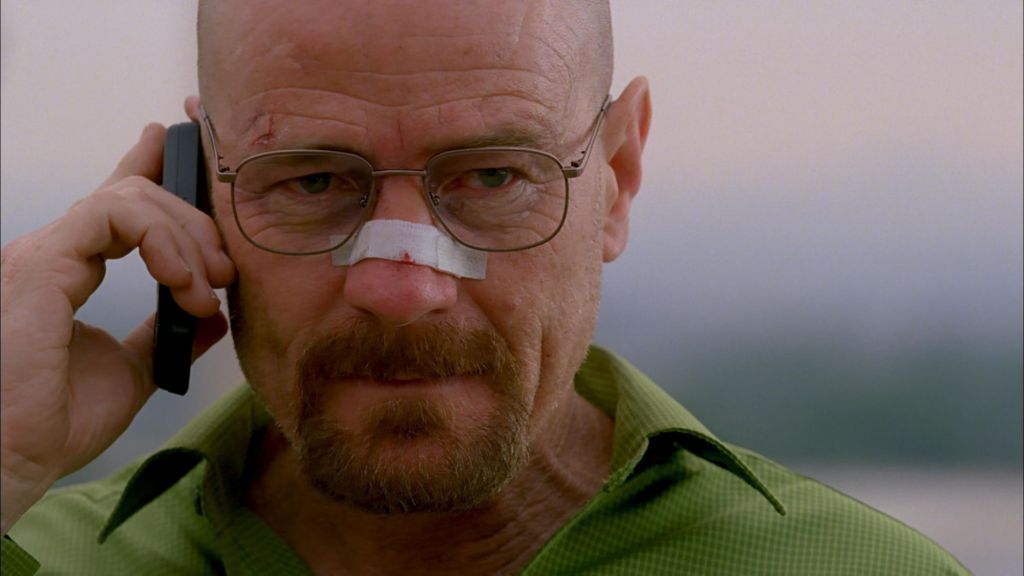

Perhaps better than any of his contemporaries, Chase always delivered meaningful, character-driven, thematically-rich, action-packed season finales to bookend each batch of 13 episodes. The season finale would become a new mile marker indicating how far we’ve come in how the television “season” had been viewed by the public; gone are the days of Farnsworth, Sarnoff, and Ball – serialization was here to stay. The Sopranos became the gold standard for how to reward audience’s trust in viewing an entire season of TV. The prestige dramas that would follow in its footsteps are perhaps too many to enumerate, but Breaking Bad is an easy jumping-off point. The 2008 show about a high school chemistry teacher who becomes a meth kingpin in order to pay for his cancer treatment not only honors the legacy of the Davids who paved the path for such gripping storytelling, but heartily continues Prestige TV’s “Age of the Antihero.” Walter White is the perfect flawed vehicle through which viewers could live out his spectacle-filled power fantasy over the course of many heart-pounding seasons. Creator and showrunner, Vince Gilligan, made a point to cap off a season in a way that offered forward momentum while also closing out a certain chapter of the overall narrative. Perhaps no better is this ideology on full display than Season 4’s explosive “Face Off” – an electrifying hour of television that positions Walter against his archnemesis, Gus Fring, in spectacular fashion. Not only does it tie up season-long threads, culminating in wild revelations and meaningful character payoffs for existing story beats, it does so in a way that honors all the build-up prior with a final hour that bookends the season with a fulfilling climax.

Its prequel-slash-sequel series, Better Call Saul, (AKA my favorite show) while perhaps a touch less known for its penchant to be explosive, still hones in on the increasingly lost art of the season finale. Take for example Season 2’s excellent “Klick,”which sees the dual narrative of the McGill brothers’ sibling rivalry coming to a head whilst residential fixer and soon-to-be hitman Mike Ehrmantraut puts the hit out on a classic Breaking Bad villain. While the show uses Mike’s connection to the criminal underworld as a portal into the thrilling violence of its source series, the legal portion can still dole out hits of equal ferocity.

The sitcom as a cornerstone of television has hardly faded into obscurity, mind you. It’s learned lessons on the structure of more serialized season storytelling as the need to adapt to its environment arose. In the ’00s and ’10s, scripted situational comedies would typically run for 22-25 episode-long seasons. Dan Harmon’s Community is a pillar of the latter, making good on genuine, serialized paradigm shifts whilst still operating within the otherwise episodic landscape of the genre. Sitcoms need a premise that will inherently generate continual whacky scenarios, and what better setting to do that in than a community college where anything can be a class or major?

And yet, regardless of genre, there has been a noticeable downtrend towards the thinning of TV seasons. Recent outings have moved the mile marker away from The Sopranos‘ prestige 13 episode season run, or even Community’s 25 episode season duration down to fewer and fewer episodes each season (looming ever closer in size to the original 8 episode first season of Twin Peaks). But why is this? Why the sudden pivot to 6 episode seasons on Disney+? There is a storied history for television and its relationship with season lengths, as society as a whole has drifted away from cable and flocked to streaming services. As high-budget productions have ballooned in cost, and the time between seasons seemingly only continues to increase, the number of episodes made during that duration seems to be shrinking. With such high profile properties such as Star Wars, how you manage the length of the season you are allotted means everything. Whereas the much-maligned Book of Boba Fett boasts a paltry six episodes (one of which is undercut entirely by a backdoor transitional season tie-in by The Mandalorian), the recent Disney+ exclusive The Acolyte focuses its also-short 8 episode run much more so on its central narrative and the characters that allow it to truly shine.

Over the course of its eight episode season, The Acolyte, while not flawless in execution, delivers a far more full-bodied experience than most of the Star Wars outings we’ve had as of late (Andor aside, of course). The building of tension between the High Republic’s existing Jedi Order, the mysterious Sith known simply as The Stranger, and a pair of twins raised by a witch cult on the planet Brendok are all given the requisite time and gravitas to add to the overall weight of the narrative, resulting in a season finale that doles out rewarding conclusions. Its eponymously-titled eighth episode speaks to the strengths of its characters, while also giving due weight to both action and revelation. Consequently, it more skillfully paves a path for its second season (#RenewTheAcolyte!!!) while also making good on the framework that its first season established over the course of its eight episode run.

The Acolyte also benefits from a weekly schedule, which is not always afforded to every show in our current pop cultural climate. Bulk-dropping an entire season’s worth of episodes has become common parlance for the likes of Netflix & Hulu, and has fostered a very different relationship with the cultural lasting power of a season of television. Tell me, when’s the last time you thought about Season 2 of Stranger Things? Sometimes it’s not the medium that’s the message, it’s the delivery; unloading an entire season at once fosters an accelerated spoiler culture, wherein the good graces of not being spoiled have been dramatically diminished over time. No longer do you have the leisure of simply consuming an entire season at your own pace, as the water cooler allotment shrinks to a paltry weekend to scarf down 10 hours of new entertainment (maybe in a single go, maybe in a few sittings, but definitely before you reach the office come Monday, wherein you run the risk of your mouthy coworkers blurting out all the most salient spoilers). Binge culture has taken a toll on our entertainment’s half-life, cordoning all discussion off into a singular weekend of rapid consumption and henceforth irrelevance. Individual episodes are swallowed whole as a binge watch experience turns an entire season of Prestige TV into a memory mush of a few standout moments with no particular segmentation in-between. I will always advocate for a weekly release schedule, as it is simply the superior watching experience, both for the health of the show itself, and for the opportunities it allows to really let each week’s episode sit with you.

Let’s talk about The Bear in the room.

The third season of Hulu’s critically-acclaimed The Bear bulk-dropped recently, and has been subject to many a headline about its unusually meandering ways. After a full-bodied second season entree that fills the viewer with hearty proteins and veggies, it even serves up a decadent dessert of a finale. Season 3, in direct contrast, seems to be more about the art of spinning plates. On the whole, it’s a much slower, more contemplative season than we’re used to receiving, and it underlines Chef Carmy’s inability to move forward. Despite the handful of standout episodes (“Tomorrow,” “Ice Chips,” and the Ayo Edebiri directorial debut, “Napkins”), there is an unusual inertness to the character drama this go around. Much of the conflict centers on a refusal to communicate, a fact which singularly embodies Carmy’s apparent regression this season. Most aggravating of all is that this batch of episodes bucks established Bear convention by being a season comprised entirely of setup, leaving viewers on a head scratching “To be continued…” Audience frustration surrounding the finale and the season as a whole speaks to the ever-shifting sands upon which a season of television resides, and what the responsibilities of a season should even be. Should the show be dedicating its time to setup and payoff, or is it a cardinal sin to offer only the buildup of stakes with little to show for it by season’s end?

And so we arrive at last night’s Season 2 finale of House of the Dragon. I have honestly had so much fun watching the past seven episodes on the couch with my best friends. The fantasy series has dedicated much of its runtime this season to the politics of the Targaryen civil war. I especially appreciate how it seamlessly wove characters into the fabric of earlier episodes whom provide a very particular in-world POV (highlighting the status and everyday conditions of low-borns in a series that centers heavily around the high-born of the realm) which go on to be of great consequence in the season’s later episodes. Episode 7’s dragon tryouts (“The Red Sowing” of Dragonseeds) is a notable highlight of the season, underlining the differences in personality between dragon and rider (Vermithor requires a brave rider, whereas Silverwing enjoys just being around a silly guy).

Episode 8, entitled “The Queen That Ever Was,” is the longest-running episode of the series thus far, clocking in at exactly 70 minutes long. And yet, as the screen faded to black and the credits began to roll, the room elicited a unanimous shout:

“WAIT, THAT’S IT?!!!”

For the entire duration, we were all pretty gripped, feeling the weight of each scene and the magnitude of each actor’s individual performances. And yet, the episode managed to feel far more like a long teaser for the third season than a proper bookend to the current one. Despite emotional beats that complete season-long arcs (notably Daemon understanding the weight of Rhaenyra’s ascendancy, and Alicent reckoning with the senselessness of her station), the looming threat of a war on three fronts closes out the season, leaving the audience to feel markedly blueballed. We will not, in fact, go “To The Gullet on the morrow!” We will instead wait another two years for the third season to make good on the promise of resolution for those dangling threads. And it raises the question: what is the duty of a season finale? Should it within reason aim to resolve emotional beats whilst also delivering bombastic spectacle? Will we settle for all buildup, no payoff? A season should encapsulate a body of episodes with a central thematic and narrative throughline (which, in fairness, HotD’s second season does achieve, insofar as wrangling dragons and riders together for the coming conflict) that pays its dues to the journeys of its characters. It should not be a preview as insurance that you’ll simply return for the next season. It should be fulfilling unto itself. It should feel like the closing of a chapter, not the book slamming itself preemptively shut. It should not be gobbled up in a single sitting. It should be allowed the requisite room to breathe and engender meaningful discussion. That’s the reason for the season.