Times have perhaps never been more daunting for creatives. The very state of our pop cultural landscape hangs in the balance as more and more external factors work their way inwards to rebut the very concept of artistic integrity. The age of social media has surely contributed to a fundamental shift in the production of new works. It has never been easier in human history to loudly disseminate one’s vocal disdain than through Twitter. The prevalence of smartphones has prompted a shift in our attention spans; we can spend hours scrolling endlessly, flittering from one topic to the next until something catches our eye for a matter of seconds, rinse and repeat.

The accessibility of YouTube and TikTok have successfully reformatted our daily (often hourly) media intake. Technology and our relationship with it has irreversibly brought about a new age of heightened studio fear and risklessness. Consequentially, works with genuine vision and unique, from-the-heart messages are all the harder to come by in the current climate. In its place with greater frequency are highly-optimized pieces of “content” that aspire only for network metrics over creating lasting art. But how did we arrive at this particular pop cultural moment? For that, we must wind back the clock.

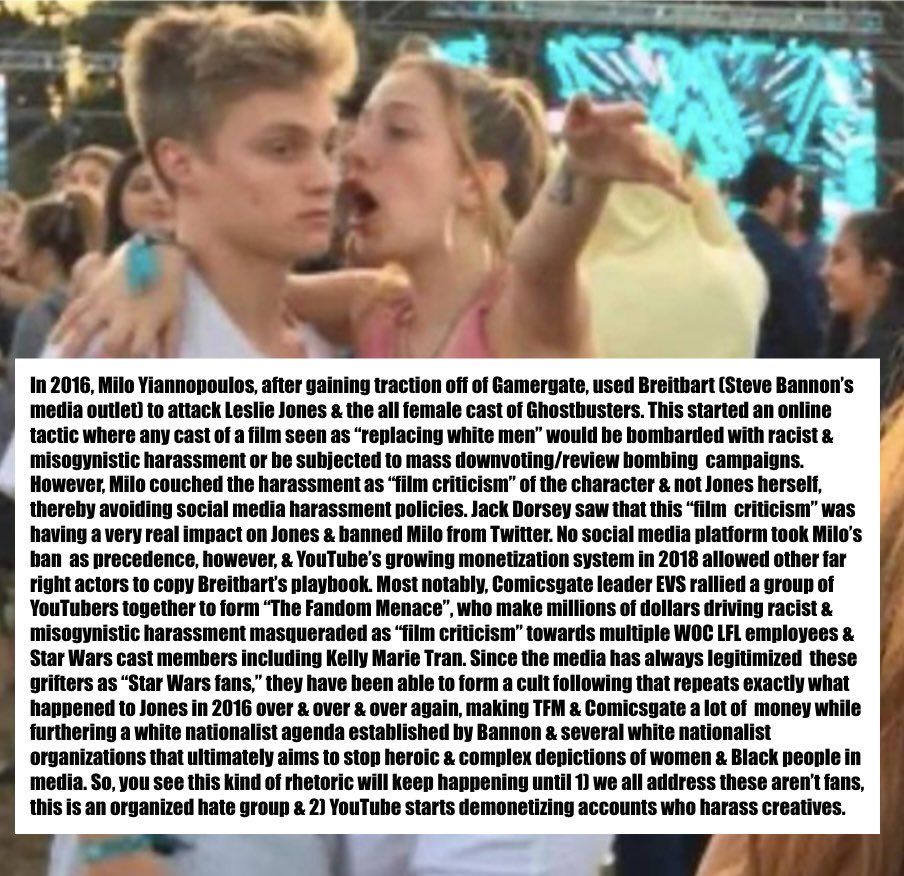

In 2014, the GamerGate controversy (learn more about the context here) laid the brickwork for the emboldening of online targeted harassment campaigns that continually weaponize misogyny and rally against “wokeness.” The original campaign laid its sights bare on female game developers who increasingly aimed to include more diverse and expansive options and storytelling choices for players, spurring the wrath of many an enraged conservative white male (the overwhelming descriptor of the average member of these hate campaigns). The trickling ramifications of this campaign can still be felt to this day. I could ramble at length about the domino effect it set into motion, but it just so happens there exists a meme that sums it up far better than I ever could:

Variety recently published an article on the current state of toxic fandom, where it is mentioned that on top of average screen testing, more and more studios are assembling focus groups of “superfans” who will vocally impart their distaste and outright warn executives of the ire that will be earned, should they continue along their current path. Handing the creative reins over to the vocal minority within a fandom who only ever aim to isolate anyone whose vision for a series does not align with their myopic, outdated perspective is how art dies on the vine. Bad faith actors who are determined to cause a ruckus both online and in test screening rooms are the likeliest candidates to flock en masse to platforms like Rotten Tomatoes and IMDB to coordinate an outpouring of negative reviews; these foolhardy attempts are often direct rebuttals against franchises being bold enough to incorporate a diverse ensemble, and/or have the gumption to question the franchise at large, as famously seen with the reaction to 2017’s The Last Jedi.

The holy war that ignited in response to Rian Johnson’s thoughtful Star Wars: Episode VIII fundamentally changed the terms of agreement to the very online discourse we continually partake in. Review bombing and YouTube hate campaigning led to a massive onslaught of “superfans” who swear they know what’s best for their beloved franchise taking to every online space possible and spreading their toxicity. At no point in their continued ramblings do they ever bother to engage with what the story is actually saying or means thematically, as delving into semiotics would be too daunting for a group this dedicated to shouting into megaphones for the dumbest, most infantile reasons. They are the ones ripe and ready for the steady stream of “content” studios are growing more eager to dish out: they want more of the Vader hallway scene from Rogue One (which they have received reimagined with their favorite action figure, Luke Skywalker, as a CGI approximation of the character lifelessly carved his way through the final stretch of The Mandalorian Season 2 finale). Catering to their sensibilities is exactly how you get colossal misfires like 2019’s abysmal The Rise of Skywalker.

It’s far from the first (nor I imagine last) time I’ve had due reason to bring up the lasting, rippling implications of both Episodes VIII & IX, and how they are as artistically diametrically opposed as two films could ever be. The latter sands off all the interesting edges of the film prior, and in its place is a maddening, empty, vapid, creatively-impoverished roller coaster that abides The Funkofication Effect. Kowtowing to bullies never results in better art; quite the opposite, in fact. All the larger questions posed by The Last Jedi are immediately discarded in favor of whiplash-inducing nostalgia bait that fails its characters at every conceivable turn. We should aspire to want more from our art than to simply deliver us those happy chemicals, and enabling “superfans” who are intent on never being challenged to have a say in the very creative process is how we lose the plot altogether.

It’s these same outraged manbabies that have been continually rewarded by weak-willed studio executives who refuse to show some backbone, deferring to this demographic to ensure that they release the most palatable, non-inflammatory version of their show or film possible. This has been the case for quite some years with Star Wars, being seen as recently as the cancellation of the Disney+ series The Acolyte. In spite of its imperfections (I hate that I have to lend that disclaimer, as if perfection is the only qualifier for a piece of art’s worthiness), the show took the existing framework of the Jedi and our understanding of The Force, and complicated it in a new and interesting way (I argue why its cancellation marks a grim portent for the franchise’s future on the whole here).

The series, led by actress Amandla Stenberg, is the latest victim of The Fandom Menace’s coordinated efforts, and despite Disney social media training its ensemble for the likelihood of vocal backlash by the usual suspects, when it comes right down to it, the actors are always left to fend for themselves. Stenberg took to Instagram last month to air out her thoughts on the cancellation of the show – a network decision that will rob the program of any definitive closure – making note of the ceaseless stream of vitriol she has been tasked with confronting on the daily. It’s these people who have been given the sway to determine what is allowed to thrive and continue on our screens. The sanctity of art, and of well-crafted storytelling pales in comparison to the power of executive cowardice. And so we are once again driven towards content – with the only remaining future projects on the Star Wars slate being the deeply unchallenging action figure fare of The Mandalorian extended universe.

Simultaneously, as studios feebly cower in an effort to minimize damage control, technology adds to the question of artistic integrity. The latest advancements in artificial intelligence in the past five years, while technically impressive, have raised many existential concerns about the role and duties of the artist within the creative process. Firstly, it must be said that generative AI is merely an input/output system based solely on the existing works fed into its own algorithm, and thus can never truly create on its own; it is an extrapolation that never credits the artists whose work it is merely approximating and regurgitating.

Consider it nothing more than a visual slot machine that spits out procedurally-generated images as a conglomeration of existing artists that will never see a red cent for their contributions. And as studios have acquired and tested this technology, many have failed to resist the opportunity to utilize AI as a means to not have to pay their own in-house artists. It exists as a cheaper alternative at face-value, but the actual pixel-by-pixel generation is so cost and resource intensive that there is a genuine ethical, ecological drawback to its usage, on top of already failing your own employees.

The incorporation of AI into the content cycle within our pop culture has already begun, with many condemning its flagrant use in the intro sequence to Marvel’s much-maligned Secret Invasion. Image generation is but one use; textual output is yet another, as seen with the controversial advertisement for Francis Ford Coppola’s Megalopolis that featured a litany of review quotes that simply do not come from existing sources. Audio generation is an additional frontier to consider, wherein even the voices of the deceased can be shoved into an algorithmic feedback mixer to ghoulish effect. The dead can never rest, for there is content to be made.

The latest viral AI marketing stunt is none other than PJ Acetturo’s AI-assisted take on a Ghibli classic. The CEO of FilmPortal.AI tweeted out a thread about how he recreated a long-imagined live-action interpretation of Hayao Miyazaki‘s Princess Mononoke with a budget of only $745. His tweets are largely meant to recruit other “AI Filmmakers” to help platform his own product, and in the process of sharing his “creation” with the world, he managed to fully miss both the point of the film, and of the medium. Live-action remakes in and of themselves often have so little to contribute to the legacy of an animated work, and one must imagine the vein on Miyazaki’s forehead throbbing. Not only does this crude estimation of a beloved work spit in the face of the animators who made it possible, but it also lacks all of the spirit, all of the vibrancy, all of the human vitality necessary for making a piece of work artful. The insistence of AI moguls trying to push their platforms to host new AI “artists” leads to a fundamental depreciation of our very definition of what constitutes art; if all you are doing is endlessly remixing the works of better, more skilled creatives without ever lifting a finger nor imparting anything of your own, you are not partaking in the creative process – you are instead pulling a lever on a randomizer. Time and again, these AI conmen seem to have one thing in common – they want all the prestige of great art, without putting in any of the effort. And perhaps it needs to be said aloud: no one is entitled to being talented. AI can only ever aspire to turn what once was passion into an insert product. Art made by nobody means nothing.

Art requires human artists, there is no getting around that. Art is a vital expression of our experiences, our fears, our hopes, our joys, our triumphs, our defeats, our growths. It can not be replicated with an ounce of believability by nameless lines of code. Even in the worst works of art, there is an immutable, tangible essence imparted by the artist that will never be present when left in the hands of AI. With artificial intelligence, all we will ever receive is the filmatic equivalent of chewed cud. And at the end of the day, that’s the core difference between Art and Content – one is created solely for capitalistic gain, and not for any greater purpose beyond that.

Doubly troubling alongside the growing concerns of AI is the overall impetuousness of studios and streaming services. Gone are the days when a show could comfortably afford a handful of seasons to find its footing and truly grow its audience – if it’s not an immediate hit, the higher ups have zero shame in pulling the plug. Just yesterday, Kurtwood Smith (of That ’70s Show fame) announced via Instagram that Netflix would not be moving forward with the sequel series, That ’90s Show, despite being the #1 trending show each week the series returned. If being the most-watched show on a streaming service does not ensure your continued existence as a series, what will at this point?

On paper, That ‘90s Show boasted every conceivable advantage on its side – staggering viewership, an established fanbase, a well-respected parent series, and even returning alumni. While it didn’t manage to capture the same lightning-in-a-bottle chemistry that first enchanted us in the Forman basement, there was something genuinely promising about the new cast members; unlike other dime-a-dozen sequel series, That ’90s Show exuded a genuine warmth that didn’t dip into reverence, nor was tainted by cynicism. It found a tasteful tonal balance in bringing the Point Place, Wisconsin of the ’70s into the age of Game Boys and puffer vests. And with that show reaching its untimely demise, who’s to say which shows will be next on the chopping block? We are at a moment in which not even the most sure-fire financial bets on pieces of media will ring true. This creates a paradoxical anxiety in the average viewer to the point where we become skeptical of even beginning a new series, for fear that it will be swiftly clipped of its wings.

But if you take one thing away from this editorial, dear reader, let it be this – there are a myriad of ways that Art as we know it is being transformed by the Content pipeline. Do not let the many claws that sink into the flesh of our pop culture discourage you, however; there is plenty of great art still waiting out there to be experienced. One of the better 21st Century problems to have is that it’s simply impossible to get around to watching everything in an age filled with such saturation. But let that be to your benefit. There is always more to discover. Take a chance on an original work. A first-time creative. Watch it. Experience it. Let it wash over you. Let the thoughts consume you until you simply need to tell a friend all about it. The very same happened to me recently with Coralie Fargeat’s stunning, repulsive, brilliant body horror satire, The Substance. I can say with confidence that I truly have experienced nothing like that film this year. Perhaps in my entire life. It inspired me to work through the backlog of Fargeat’s filmography, which only extended the joy.

So never mind all the GamerGating. All the Fandom Menacing. All the AI slop. There are plenty of meaningful, worthwhile works of art out there for us to explore. And perhaps…even let the art that you experience inspire you to make something original of your own.

The Age of Content is only as strong as our refusal of it.

We need Art, but Content needs us, and not the other way around.